Blowing Open the Door on 2025

Puppet Imposters -- Story Machines -- Roving Gangs -- Shuffled Decks

Out picking up ingredients for Christmas dinner, I made a last-minute impulse buy: a pair of blind-bagged Dungeons and Dragons Lego minifigs for me and my partner to crack open alongside our other presents. I’ve a soft spot for ‘what’s in the box’ toys, especially when it’s variations on a theme, especially when that theme has a tangential connection to something I’m working on — and minifigs don’t take up a lot of space.

When it came time to reveal the contents, I found myself putting together a sort of Mesoamerican priest, with robes of fiery orange, green and gold and a feathered mask. The figure ‘floated’ atop a transparent brick and carried a translucent cube or die with a diagram of a mountain range on one side. I wasn’t sure who or what it was meant to be, so I did a bit of research. To my delight, it turned out to be The Lady of Pain, an unseen background character from Planescape: Torment, one of my favourite games of the 90s. She’s the ruler of Sigil, City of Doors — a hub at the centre of the multiverse containing portals to every possible plane of existence. Not a human, not a god either — no one knows what she is. Her die is a ‘cubic gate’, a means of opening further interdimensional portals, and what I’d taken for feathers were, in fact, sparkling blades; those who meet her vanish onto a maze, or become covered in lacerations.

Strange choice for a children’s toy, but a perfect miniature totem for me, thinking back on the year just gone and where to turn my focus going forward! Gateways, doorways, nodes and connections — these have become increasingly important themes in my writing and teaching (eg. the titles of the last two pamphlets I brought to international conferences: Hidden Entrance and Steal Through the Gap in the Hedge). There’s good reason for this: everything that weighs on me, that is a cause for grave worry — the ongoing diminishment of the arts and instability of the university sector, the disastrous tepidity of centrist policymaking, the growing numbers needing support for illnesses and impairments, the racialised murder sprees sanctioned by my government, the toxicity of social media and so on — all of it is tied to a thinning of possibilities, a barricading of doors and filling in of passageways.

That is to say, the failure and volatility of market capitalism has produced louder and more frequent demands that we simply make do with less, stay in our individual pens and think of little beyond toiling away. Everything else is deemed frivolous and punishable. Conservative reactionaries, whose representatives keep securing stronger and more permanent footholds in power, are not shy about outlining their vision for civilisation: dramatically less emigration, education reduced to vocational training, no social safety net, no experimental art, no politics or philosophy in our entertainment media — no politics at all, in fact, outside of nationalist propaganda. The message is clear: we should no longer think of social improvement, except via those technological cures beloved of the culturally disengaged, which encourage emotional isolation and remove ever more autonomy from the workforce.

Not coincidentally, my third article for The Conversation — by far the most popular in terms of reads — was about the recent Porter and Machery study showing people can no longer tell the difference between AI poetry and that written by humans. The article is hopeful rather than angry; I dismiss the idea that there’s any threat to the existing demand for human-written poetry, paltry though that demand is. But the offensiveness of AI poetry doesn’t really have anything to do with how good the poetry is, or how easily it fools us; rather, it’s the very idea that poetry should be viewed as a product, an output. This makes it a matter of routine, something that might as well be done mechanically, as opposed to an engine or cognitive process, a way in which we generate new ideas and ways of thinking.

In turn, this makes me think of one of the books I finished reading toward the end of the year: Adolfo Bioy Casares’ The Invention of Morel, in which a fugitive discovers an island full of facsimile humans who play out the same sequence of actions every day. They turn out to be the solid-light projections of an advanced recording and playback device. The inventor of this device, Morel, wants to preserve his friends and the object of his desire for all eternity. In using it on them, though, he accidentally kills them, replacing them with lifeless dolls that only convince as humans to the degree you don’t directly interact with them. Not far off the corporatist-conservative ideal, then: everything captured and replicable, predictable, hard-coded. Nothing left to chance.

Chance is a doorway. Randomness and unplanned — or only loosely planned — meetings are a route to new opportunities, potential ways forward. That’s why a roll of the dice can be so exhilarating — sometimes it nudges everything into place. And that’s why I jumped at the chance to be a part of Collusion’s ART / TECH / PLAY event in November, despite a ridiculously busy term and the fact that I’d said yes to doing another presentation just a week later. For this event I wanted to talk about card game poems, or what chance mechanics bring to poetry. I brought my long-abused prototype of Whispering Leaves (in which doors are a prominent visual motif, the leaves in question being door leaves), along with some new, just-about functional digital simulations of other card games.

But the real joy was mixing with other practitioners in the same area, include Danny Snelson, who was coincidentally in town for a lecture on ancestral intelligences in visual culture, delivered by his partner, Mashinka Hakopian. Danny’s work combining poetics and gaming/VR technologies slotted neatly into the theme of the night, alongside talks by Jon Ingold, narrative director of Inkle and writer of Heaven’s Vault, and Laura Trevail, a ‘contextual artist’ — someone who combines tech, writing and visual art in response to specific sites and situations.

Laura’s work had been recommended to me not two weeks earlier, by the poet Sarah Wedderburn, on the way back from another gig which I’d said yes to in spite of the heavy schedule — this time involving a five-hour round trip to Oxford on a Monday night. This gig, organised by Helen Eastman of Live Canon — long-term stalwarts and allies on the poetry scene — took place at the Former United Reform Church, and due to a last-minute change of readers, I found myself following up Glyn Maxwell, the poet whose work had first inspired me to throw myself into poetry, age 17. More doors: present to past, from one kind of performance to another, conversation to conversation.

Due to an unusual and painfully costly arrangement with our Scottish distributor, I now keep several boxes of Sidekick Books stock in my garden shed for posting; as a result of this, we are now officially — I would say, anyway — an East Anglian as well as a London-based publisher. This qualified us for a spot at the Norwich City of Literature Christmas Publishing Fair — back in the city where Kirsty and I first met and started making lit magazines together. We made some good sales, including of the new Ten Poets series.

Which brings me on, finally, to some projects forthcoming in 2025, while continuing the theme of portals and crossings. Out very soon with Calque Press is Ragged Band of Travellers: Writing from the Threshold of Dungeons and Dragons, taking us right back to the opening topic of this post. This is a short anthology of poems and stories written for one of our Future Karaoke nights at ARU, with some extra pieces by George Herbert, Christina Rossetti and Edmund Spenser sprinkled in, the idea being to cover a whole bunch of the D&D classes and species. The title and theme evokes the idea of different people with different backgrounds coming together, and chance meeting leading to adventure. A preview snippet from my introduction:

For my part, I believed then (and do now) that the relationship between distinct-but-adjacent voices is just as important as what any one voice conveys to a reader or listener, especially where there are gaps and awkwardnesses to be reckoned with – where the voices could almost be bickering. (…) As such, you’ll find there’s no common setting to the pieces in this anthology, nor any shared lore informing them. This is not a love letter to D&D, or a commemoration. The way in which these poems and stories work together – belong together – is instead akin to the way the spells, skills, attacks, traits and equipment of different player characters combine in sometimes useful, sometimes surprising ways that must be tested to be discovered.

The next Future Karaoke, meanwhile, is likely to be in early February, on the theme of mixology.

As for Sidekick and Ten Poets, the series has been successful enough for us to think about making it a regular thing, and as such, we are currently reading through the results of our first open submissions call in three years. Four submissions will be chosen to be published alongside six commissioned pieces to make up Ten Poets Travel to the Dark Side of the Moon, out at the end of April. I’ve been seriously impressed with the range and quality of everything sent in, and the number of ways different poems could be fitted together to make completely different kinds of book is making my head spin somewhat. Onto the shortlist!

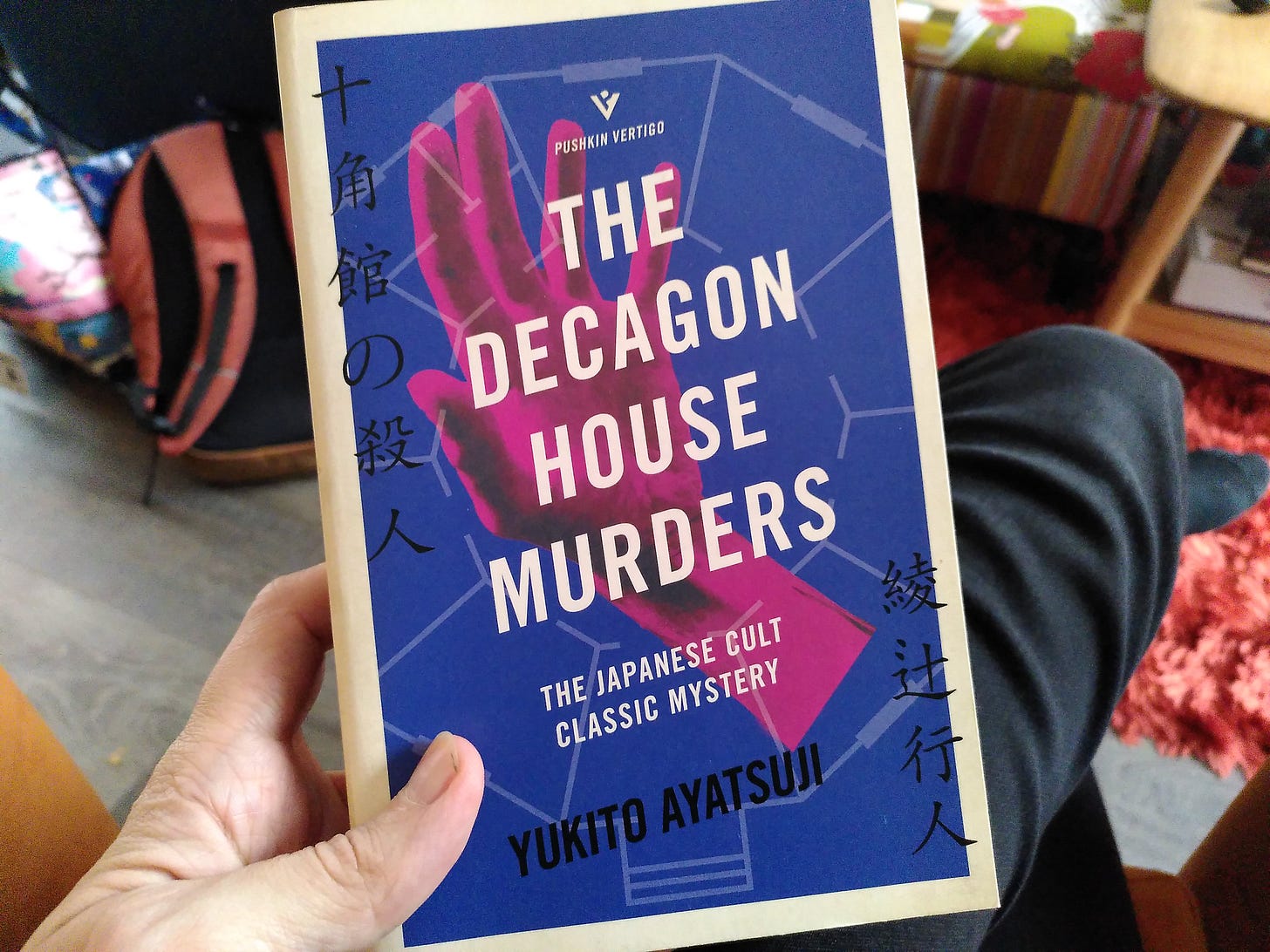

I’m going to finish up with a shot of one of my Christmas presents — The Decagon House Murders by Yukito Aatsuji — in order to keep with the regular pattern of Stray Bulletin cover images. It’s a book which converses with the past (all the main characters are named after golden age crime writers) while rearranging those familiar elements just enough to make something new. That’s the kind of business we need to keep up, right? Happy New Year!