"Like a pair of thin keys"

Dark bedrooms -- Sexy fireworks -- Horrible strangers -- Aromatic grasses

With the teaching semester nearly over, I have a moment — at last! — to reflect on some recent developments.

Hobgoblin Mode

Things have been a little dry on the publishing front — at least when it comes to new poems of mine, out on their own. But earlier in the year I was drawn to Mark Antony Owen’s After… project — a journal of ekphrastic poetry which publishes a single new piece every full moon. My poem, ‘Not Receiving Visitors’, based on Sidney Sime’s The Incubus (1899), was revealed on 17th October. I’m not sure exactly where it fits in to the various forthcoming or in-progress collections I’m hoarding, but here is the opening:

Lately I have lain awake while a lamp throbs and flutters, my face turned upward into a pool of dark – as if that pool had been lowered like a scrim, or a coffin into its pit.

So Long, Moral Seriousness!

Since I haven’t been publishing a lot of my own work lately I also haven’t had a lot of critical feedback, so it was rather thrilling to find that my debut collection, School of Forgery, is mentioned in Andrew Duncan’s new Shearsman volume, Beautiful Feelings of Sensitive People: Screen Grabs of British Poetry in the 21st Century. If the title sounds dismissive, that isn’t the intent; Duncan’s starting point is that ‘beautiful feelings of sensitive people’ is, broadly, what people expect of poetry and poets — that any more sophisticated understanding of what the art can achieve has lost its grip on the collective conscience … for now. This is in part due to the sheer abundance and variety of poetry being published, such that any other general characterisation runs into trouble immediately.

His ‘screen grab’ approach is refreshing. Rather than presume to pick out a few poets as the leading lights of a generation, thinning the herd in order to tell a neat story, he accepts that any serious expedition into the landscape of contemporary UK poetry “can last for years”, and involves travelling through many ‘micro-climates’. The book is therefore a series of snapshots from one such expedition. When he comes to School of Forgery, he finds the key to the book is the poem about Bleach dōjinshi (fan comics in which the characters often enjoy intense romantic liaisons), adding:

Stone seems to prefer inauthenticity, but this allows him to jettison the apparatus of realism and moral seriousness, so that the poems have a wonderful lightness, bursting like fireworks.

It’s a huge book, covering 80 poets in all, and so far I’ve only read the entries for about a quarter of them.

Real Talk

It seems I’ve taken up writing articles for The Conversation, in the hope of reaching a new audience and building up my academic credentials for the next annual review. They favour a very short kind of article — which suits me very well — with very short sentences and paragraphs — which I’m not so hot on. I’ve never had my writing edited quite so severely, and am still getting used to the effects. On the other hand, the editors are very friendly and efficient, as well as receptive to pitches.

My first two articles are: 1) a quick look at the idea of adapting a video game into a poem, mostly drawing on research I’d already done for the PhD, and 2) a round-up of giant monster poems. The latter is the kind of article I’d like to write more of, going forward. Yes; listicles. Poetry listicles.

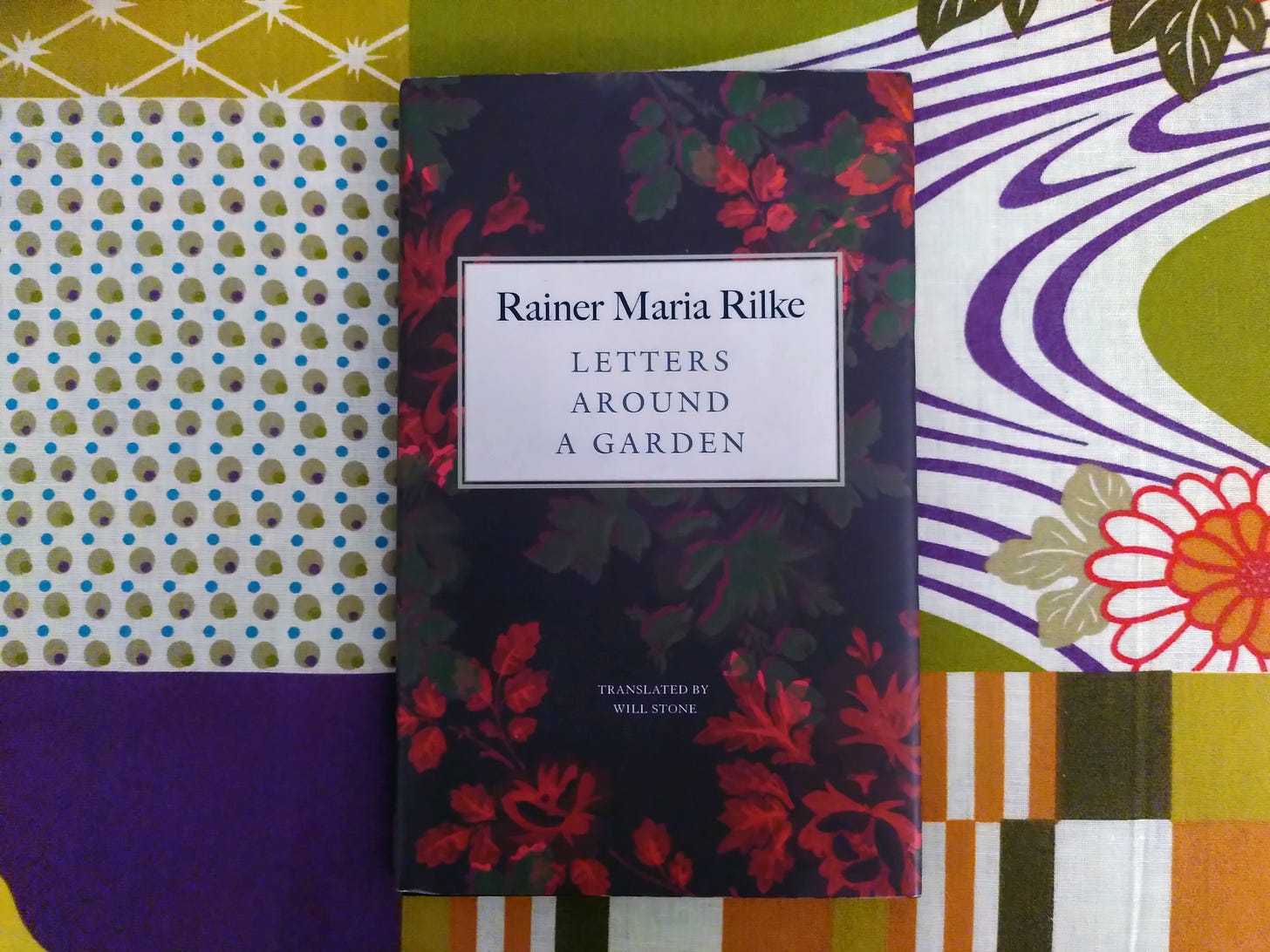

Muzot, 1924-26

Toward the end of the summer, I decided to pick up Will Stone’s translations of some of Rainer Maria Rilke’s last letters, published as Letters Around a Garden. I’ve got my own garden now — not that I’ve made much progress with it — and am picking my way little by little toward my own garden-themed book. Even more painstakingly slowly, I’ve been making my way through the Rilke.

It’s an odd book; the letters are addressed to one Antoinette de Bonstetten, from a chateau in Muzot, Switzerland. Rilke is in exile, and earnestly seeking de Bonstetten’s expert help in establishing his garden. Her replies have been lost, and his various reports, musings and pleas are so scattershot that he comes across as something of a hermit romancing a ghost. He is besotted with his garden, with de Bonstetten (whom he has never met), and with everything else besides — almost a cartoon sketch of an eccentric old poet. Here he is in letter no.12:

Dear Mademoiselle,

Is it, is it really possible! And I who continue to conceive these little Provençal plans for you; it’s true that you have (invited to this sudden decision) concentrated the juice of ripened farewells and made more arduous the beautiful and sorrowful face of departure. And why would you not, at the same time, have obliged the honour of destiny to arrange for you a happy return?

Occasionally, his writing on the Swiss climate or a species of flower is wonderfully crisp:

Here, when the sky is obscured, the breath of snow which comes down the mountains immediately expunges any aspirations the rain may have had. It rains awkwardly, and the sky inscribes these few lines in the air, without pleasure, like a schoolchild with fingers frozen stiff.

I feel, though, as if I’m foraging in a mind and life so foreign to my own that I’m almost nodding along out of pained politeness. It makes me wonder to what extent we expect poets to be people like us, and to what extent we intentionally reconstruct them as otherworldly figures.