The year’s nearly done, and this is the first of two planned posts picking out some highlights from all that I haven’t found time to blog about over the last six months.

Creels and rockpools

Although I’ve made a start on countless digital ‘ludokinetic’ poems over the last five years, hardly any of them have reached a complete, publishable state. Too much tinkering still required! Also, there’s hardly anyone to publish them with. The New River are one of the few outposts for such projects, and I’m very grateful to editors Amanda Hodes and Florence Gonsalves and their team for taking on ‘I could kiss, say,’, an interactive eco-poem in which you, the reader-player, get to romance the natural/unnatural landscape. Turn your sound on — there’s vocals and a little synth music to go with the movement and play.

Dust and honey

I wanted to write so many more reviews and responses to books and individual poems this year! More than that, I want to start proving and exemplifying that reading and critical writing can and should be as expressive and creative as what we deem ‘creative’ writing. You’ll know if you’ve been following my thoughts on this subject that this is because I value poetry and art as an ongoing, inclusive conversation and that my bête noire is the idea of the poet, the writer, the artist as the one who speaks for, at or over the top of others.

But drafts and notes have mostly failed to coagulate into finished, publishable pieces — except in the case of one more ‘Single poem round-up’ where I investigate poems by Sarah-Jane Crowson, Kate Crowcroft and Callie S. Blackstone, published online in Stone Circle Review, Berlin Lit and Rust & Moth respectively. There are links to the pieces in question, so that you can read them in one browser tab and follow my thoughts on them in another.

Short extract from the review itself:

These are all poems about love, of one sort or another — though look what happens to the personal pronouns as each unfolds […] In all three, the traditional pose of the love poem quickly gives way to something more febrile, some more insistent energy which leaves me reaching to pull together the fragments.

Stereograms and anagrams

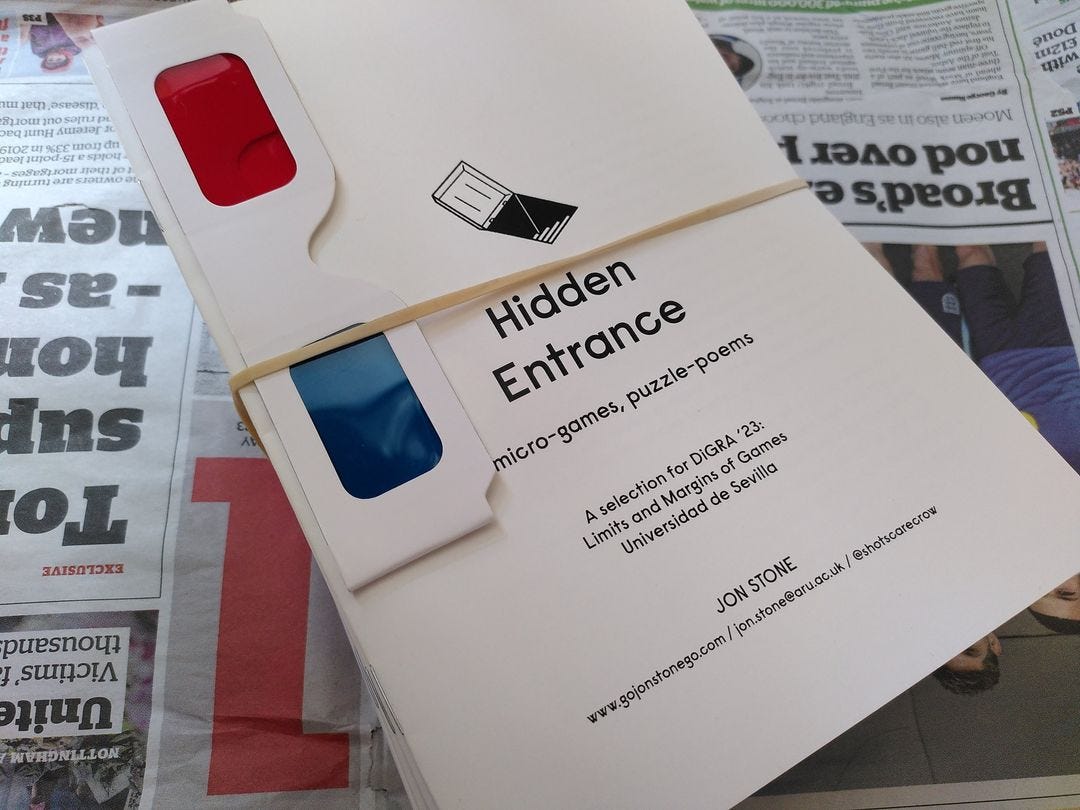

In the long-gone summer I made my way to Seville to present a paper at the DiGRA (Digital Games Research Association) international conference. I’ll get to the paper in a later update; for now, I’d like to link you to a digital copy of Hidden Entrance, a tiny pamphlet I put together to hand out to other attendees:

As well as a QR code linking up ‘I could kiss, say,’ and extracts from last year’s Look Again: A Book of Hidden Messages, it includes three brand-new, one-page ‘role-playing’ poems based on recent video games Sable, Citizen Sleeper and Stray.

To my knowledge, no one yet has solved the anagram on the final page. Perhaps I should offer a cash prize?

Flirtwort and fossils

The Excavation of Hob’s Barrow has been termed a gnostic horror game — not normally the kind of thing that attracts my attention (too many horror games are just slavish adaptations of Lovecraft, or zombiefests). In this case, though, a few things swayed me: it’s a traditional point & click puzzle adventure, utilising primitive-looking graphics to unsettling effect; it’s more indebted to M. R. James than Lovecraft, dealing in the obsessions of a Victorian archaeologist; and it’s set in Bewlay, a fictional village just down the trainline from Bakewell. This does not place it, as some players seem to think, in the Yorkshire Moors, but rather in the Peak District, close to where I spent most of the pandemic.

The script and voice-acting is generally of a high standard, with only the odd dodgy accent, and the story is well-paced, becoming gradually more uncanny the more you uncover of the protagonist’s background and present situation. The backdrops are wonderfully bleak, capturing the feel of the Peaks on a foggy day, and the occasional close-up animation is richly disturbing. Impossible not to think of The Wicker Man as you weigh up the likelihood that the residents of the village are conspiratorially toying with you, keeping the answers just out of reach. The point & click genre lends itself well to this kind of tale, since its puzzles are always so oddly contrived — must I really jump through all these hoops just for some puddings, a horse hair, a pail of goat’s milk? Yes — because in this case, it adds to the sense that you are being led, step by step, toward some grim fate.

As to the ending, I was left a little unsure. It might be that the story lost its footing in the final act, becoming overly predictable, or it might be that I just wanted a little more agency in a supposedly interactive medium. This aside, The Excavation of Hob’s Barrow is one of my favourites of the games I’ve played this year.